By Amy Novotney

American Psychological Association, 2009

Vol. 40, No. 1, Page 50

New research shows that privileged teens may be more

self-centered—and depressed—than ever before.

Many of today's most unhappy teens probably made the honor

roll last semester and plan to attend prestigious universities, according to

research by psychologist Suniya Luthar, PhD, of Columbia University's Teachers

College. In a series of studies, Luthar found that adolescents reared in

suburban homes with an average family income of $120,000 report higher rates of

depression, anxiety and substance abuse than any other socioeconomic group of

young Americans today.

"Families living in poverty face enormous

challenges," says Luthar, who has also studied mental health among

low-income children. "But we can't assume that things are serene at the

other end."

Privileged teens often have their own obstacles to overcome.

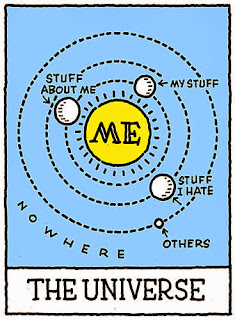

Some say these problems may be due to an increasingly narcissistic society—as

is evidenced by fame-hungry reality TV stars and solipsistic Web sites. Plus,

says Harvard University's Dan Kindlon, PhD, families have shrunk and kids are

now seen as more precious.

"It was kind of hard to think that the world revolved

around you when you had eight brothers and sisters," says Kindlon, author

of "Too Much of a Good Thing: Raising Children in an Indulgent Age"

(Hyperion, 2001).

Others say the trouble may stem from parents who put too

much emphasis on grades and performance, as opposed to a child's personal

character.

"My experience with upper-middle-class moms is that

they are worried sick about their kids," says San Francisco clinical

psychologist Madeline Levine, PhD, author of "The Price of Privilege: How

Parental Pressure and Material Advantage are Creating a Generation of

Disconnected and Unhappy Kids" (HarperCollins, 2006).

While such parents are certainly well-meaning, it may take a

toll on their children.

Generation all about me

When Levine first began lecturing to parents about child

rearing, she titled her talk "Parenting the Average Child" and had a

hard time attracting a crowd, she recalls. "Nobody believed they had an

average child," she says.

But parents aren't the only ones insisting their children

are special—their kids believe it as well, according to research by San Diego

State University psychology professor Jean M. Twenge, PhD. She analyzed the

Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) scores of 16,475 American college

students between 1979 and 2006 and found that one out of four students in

recent generations show elevated rates of narcissism. In 1985, that number was

only one in seven.

Some narcissistic traits—such as authority and

self-sufficiency—can be healthy, says Robert Horton, PhD, a psychology

professor at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Ind. But too much

self-absorption can often lead to interpersonal strife, he adds. Research shows

that narcissists tend to be defensive, do not forgive easily and have trouble

committing to romantic relationships and holding on to friendships. In other

words, their egos can get in the way of true happiness, says Twenge.

"Narcissism is correlated with so many negative

outcomes," says Twenge, whose research appeared in August's Journal of

Personality (Vol. 76, No. 4). "Yet it seems to be something that is now

relatively accepted in our culture."

Our culture's cult of celebrity may fuel the fire. In 2006,

Drew Pinsky, MD—a radio host and psychiatry professor at the University of

Southern California—teamed with USC psychologist Mark Young, PhD, to measure

celebrities' narcissism levels. Two hundred well-known actors, musicians and

comedians completed the NPI. The researchers found that celebrities were

significantly more narcissistic than the average person. The study, published

in the Journal of Research in Personality (Vol. 40, No. 5), also showed that

reality television stars were among the most narcissistic of all celebrities.

"These shows are a showcase for narcissism, and they're

portrayed as reality," Twenge says.

Psychologist Susan E. Linn, EdD, fears that today's

fascination with wealthy celebrities and reality shows such as MTV's "My

Super Sweet 16"—where a teen plans a million-dollar birthday

party—contribute to normalizing this type of behavior. Kids immersed in this

kind of media glitz feel unfulfilled or even like failures because they are not

fabulously rich or famous, she notes.

"The combination of ubiquitous and sophisticated media

and technology and unfettered commercialism is just a disaster for kids,"

says Linn, associate director of the Media Center at the Judge Baker Children's

Center at Harvard University. "A constant barrage of images of wealth and

narcissism promote unhealthy values and false expectations of what life should

be like."

Harvard or bust

Psychologist Kali Trzesniewski, PhD, however, isn't

convinced that narcissism is really on the rise. Her research, based on a data

set of high school seniors from across the country as well as college students

at the University of California, finds that students answer the NPI the same as

their counterparts 30 years ago. She says what may seem like self-absorption is

probably just more awareness of the numerous choices now available to them when

it comes to what they want to do with their lives.

"Graduates entering the job market today have a lot of

opportunities and a lot more jobs to choose from, so they have the freedom to

be more selective," says Trzesniewski, a psychology professor at the

University of Western Ontario, whose study appeared in February's Psychological

Science (Vol. 19, No. 2). "That doesn't necessarily change their core

beliefs."

Levine believes that what's actually driving

upper-middle-class teens' mental health troubles is a fear of failure. Parents,

she says, worry that their children won't make it in an increasingly

competitive world, leading to an obsession over standardized test scores and

getting their kids into the right schools.

"Parents are worried that if their children don't get

into Harvard, they're going to be standing with a tin cup on the corner

somewhere," Levine says.

On top of perfectionism, teens often can't deal with

situations that don't go their way, perhaps because their parents protected

them from disappointments earlier in life, Levine says. In fact, teens who

indicated that their parents overemphasized their accomplishments were most

likely to be depressed or anxious and use drugs, according to a 2005 study led

by Luthar in Current Directions in Psychological Science (Vol. 14, No. 1).

What can parents do? Levine and Kindlon recommend that they

give their children clear responsibilities to help out around the house and

that families take part in community service activities together. Turning off

the TV at least one night a week and monitoring Internet use are also

important, says Linn. Such actions teach children the values that can lead to

greater life satisfaction, says Levine, who also urges parents to stop

obsessing about perfect grades and focus more on helping their children enjoy

learning for its own sake.

And parents and psychologists alike should recognize that

teens who seem to have it all may, in fact, lack the resources they need to

find personal happiness.

"We've been a little remiss in assuming, without much

examination, that children of privilege are immune to emotional distress and

victimization," says Luthar. "Pain transcends demographics and family

income."

Further reading

- Kindlon, D. (2001). Too Much of a Good Thing: Raising Children in an Indulgent Age. New York, N.Y.: Hyperion.

- Levine, M. (2006). The Price of Privilege: How Parental Pressure and Material Advantage Are Creating a Generation of Disconnected and Unhappy Kids. New York, N.Y.: HarperCollins.

- Twenge, J.M. (2006). Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled—and More Miserable Than Ever Before. New York, N.Y.: Free Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment